“I challenge you to a duel!” Those words can be heard as an echo throughout history, often ringing alongside as part of the entertainment. The fact that many people enjoy depictions of stylized combat is nothing new. Just ask the ancient Roman gladiator and the modern MMA athlete.

Yet, nowhere in history can stylized combat be found more heightened and romanticized than in action cinema. The journey that combat movements have blazed through entertainment has been a long and arduous one, weaving in from staged combat in old theatre to high-octane modern Hollywood and worldwide action cinema. Let’s take a dive roll through the ages in a short History of Fight Choreography – Part 1: The Olde Days!

Kickin’ it Olde School!

Would you be willing to learn from a clown? What if that clown happened to hold the unique position of being Queen Elizabeth I’s favourite jester, a member of William Shakespeare’s acting troupe, and was credited as a fencing master?

Richard Tarlton: Pioneer & Early Modern Fight Director

Enter Richard Tarlton, a man whom many consider to be the first modern fight director. Blackfriars Theatre in London was the talk of the town. Home to many great actors and plays, innovations seemed to nestle its head often in this popular, high-priced theatre, showcasing a reliance on artificial lighting and even musical pieces being played between acts. It wasn’t always this grand however. In fact, it was a shared space between many. A guild of fencing masters frankly named, Masters of Defence, also once held residency, evidenced to have at least co-habited for a few years after the theatre leased around the year 1576.

Naturally, cross pollination began to happen at Blackfriars Theatre. Richard Tarlton was an actor in the famed William Shakespeare’s acting company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (later called The King’s Men). Aside from acting, he had skills in dance, music, comedy, writing, and fencing. He studied with the fencing masters in the area and learned from them greatly, eventually becoming credited as a fencing master himself. These skills did not go unnoticed by Shakespeare. Tarlton’s skills made him unique in that he could not only play many roles doused in combat prowess, he could also help other actors refine their skills in fighting for the stage.

While fighting had not been missing from stage plays prior to the late 1500’s, it was new to have somebody available who would coach and refine the stage combat the way Tarlton could. Throughout the next few centuries, European fencing masters would continue to experiment with various weapons and work alongside actors to enhance the stage combat experience.

Douglas Fairbanks & “The Mark of Zorro” (1920)

The second renaissance for choreographed sword fighting came during the advent of silent cinema with a gentleman named Douglas Fairbanks.

The film “The Mark of Zorro” (1920) set itself apart from the rest by hiring a fencing master and crafting sword fight choreography that actually resembled legitimate fencing.

Enter The Errol Flynn!

With that being said, these still weren’t action films that you’d devour a whole bucket of popcorn over. These were fairly basic fight scenes. It wasn’t until Errol Flynn came along that these fights got a lot more dramatic.

The 1932 big budget swashbuckler film “Captain Blood” showed audience members something dynamic. The fight scenes utilized the environment more, showed close ups and diverse angles, and carried an interesting rhythm. These captured the audience’s attention and kept them prisoner like a merciless pirate.

While a duel with weapons would always enrapture, empty-handed fight scenes were gradually developing at this time as well. The problem with fight choreography for stage and cinema—be it empty handed or with weapons—is that what looks spectacular is often not exactly those practical techniques rehearsed in martial arts. Proper technique in a fencing duel is comprised also of small and efficient movement, not simply the large and elaborate movements that are perceivable by audiences. Adaptation was needed and methods had to be created to better capture the movements of fine tuned combat in an appealing way.

Thankfully, combat as a safe and entertaining performance was evolving elsewhere around the world at the same time, not least of all, in Asia.

The Evolution of Dramatic Action Worldwide

Each place did its own thing. The Minangkabau people of West Sumatra were combining dance, music, drama, and Indonesian martial arts—known as Silat—in their Randai folk theatre.

A Southwestern region of India was showcasing Kathakali, a classical Hindu dance performance that drew inspiration and body skills from the Keralan martial art of Kalaripayattu.

Kabuki: Theatre of Classical Japanese Drama & Dance

Of course, Japan was also home to performances and oh, what a stylized performance it was that they were crafting! Kabuki is one of the old forms of Japanese theatre, requiring its actors to learn and perfect many artistic skills. Within that performance skillset, sword fighting skills were a must.

These kabuki fight scenes were known as tachimawari and were viewed as dramatic pieces rather than just adrenalized action. In fact, contact was not always made in the sword battles. The reactions and emotions of the actors were instead what would sell the hits and slashes.

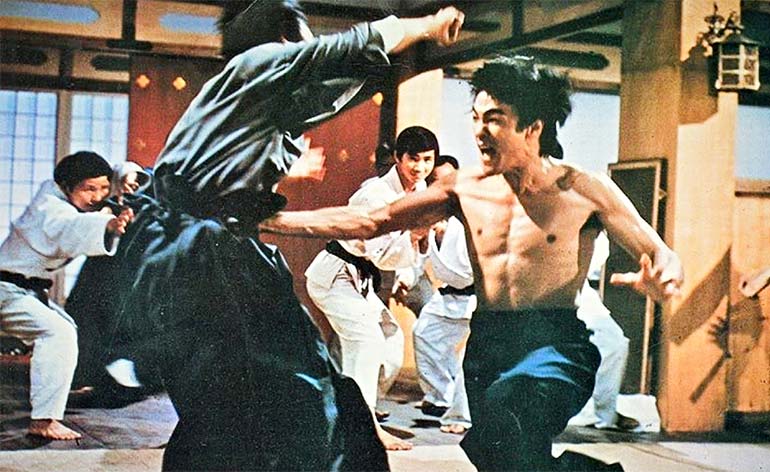

The fights would often, though not always, be the masses versus the hero. As many as thirty attackers would attempt to take down or capture the protagonist—utilizing poles, swords, ladders, or even roof tiles—only to be deftly and graceful dealt with.

Kabuki deaths were exaggerated acts, many times showcasing slow agony if the character was a prominent villain. If in an en masse fight scene, the dying character would typically perform an acrobatic tumble, known as tombo gaeri, into a lake or off of a platform, the actor having learned how to land safely so that he can come back later in another role. Once the fighting subsided, the protagonist would assume a mie, or pose, taking an extravagant posture highlighting the character’s victory.

Though the tempo of the fight would depend on the play, it was never a hurried pace. Rather than fast aggression being shown, each fight would be choreographed to music played offscreen by shamisen and drums. The role of fight choreographer was titled tateshi and required the person to have knowledge of numerous movement patterns and mie.

As some of the first films were adaptations of classical kabuki plays, this form of stylized combat performance would later carry over into cinema, especially the genre of Jidaigeki (period era films) and their offshoot, chanbara (samurai films).

The Samurai Swagger

Following the heels of World War 2, the 1950’s and 1960’s were a chanbara (Japanese for sword fighting/samurai films) goldmine, putting the spotlight on real life samurai (such as Miyamoto Musashi) and fictional ones (such as Zatoichi). Interesting to note, this was also the time of cinematic give-and-take between the East and the West.

The chanbara genre was to the Japanese what the Western genre was to Americans. They both depicted warriors of the past following their personal code of ethics and fighting for honor and justice. The chanbara and the Western films could be seen as two sides of the same coin, often complimenting each other in unexpected ways.

Western filmmakers such as the legendary John Ford would go on to inspire and influence directors for the chanbara genre. Many of these chanbara directors would later achieve massive success, some such as Akira Kurosawa even garnering further popularity overseas. Interestingly enough, many of these Japanese films would later get remade later as a Western, trading swords for firearms and masterless samurai for outlaws of the wild west.

A great example of this evolution is Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 film, “Shichinin no Samurai”, or Seven Samurai. This film would go on to be celebrated worldwide and remade and referenced many times over. Just six years after its release, it was remade as an Old Western film entitled “The Magnificent Seven”, itself becoming a popular film that still garnered sequels and remakes over half a century later…